K-Democracy

South Korean Democracy Didn’t Happen by Chance

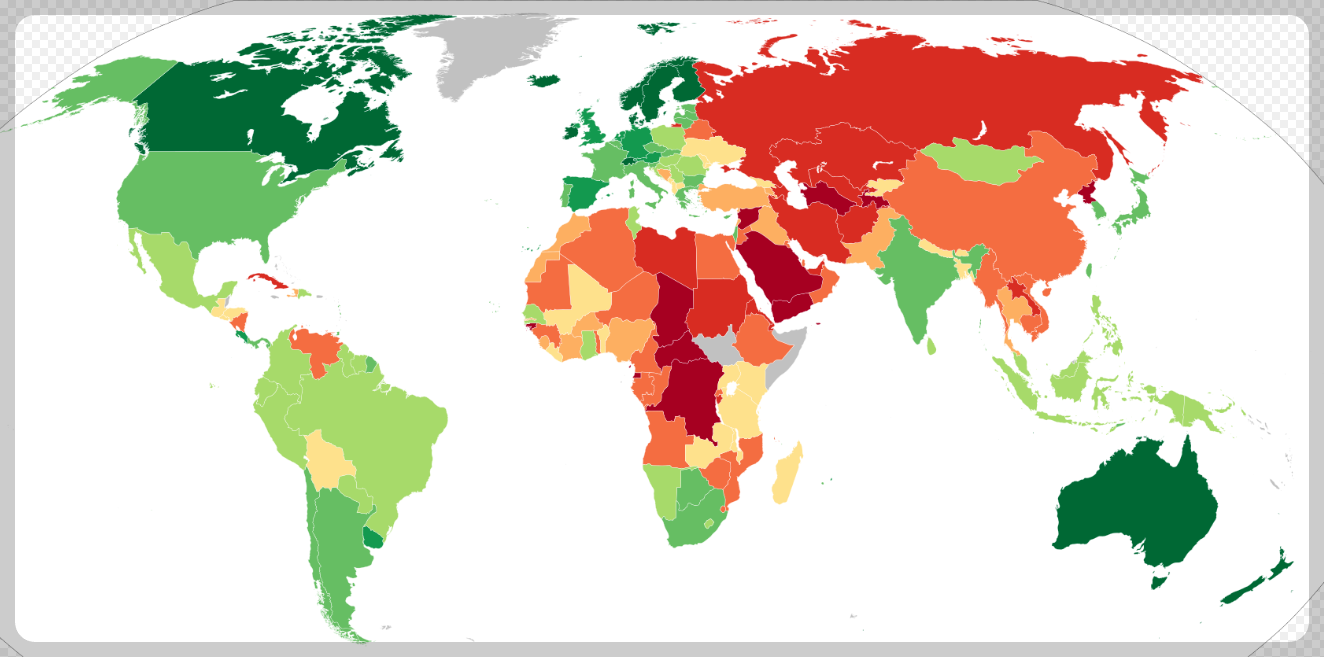

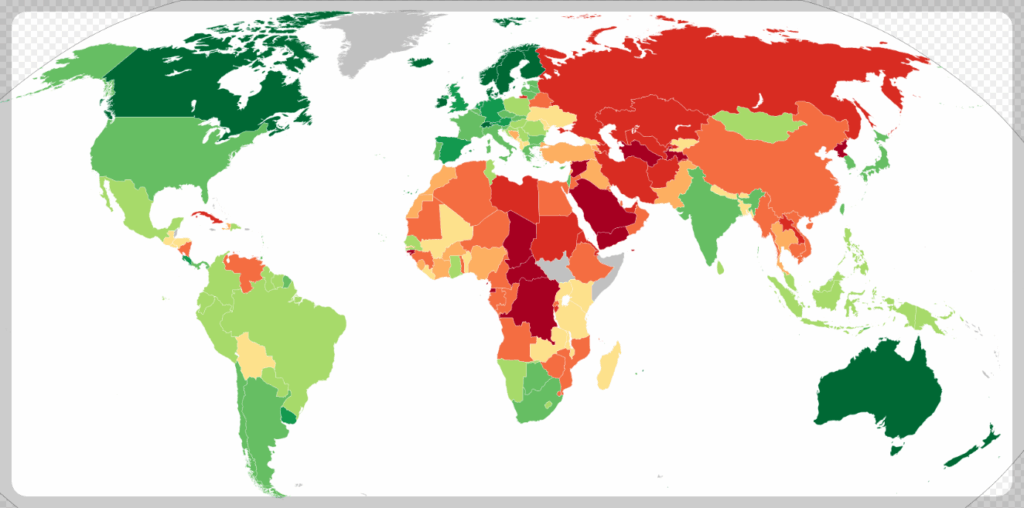

South Korea today is often hailed as one of the fastest countries to transition into a stable democracy in modern history. Just a century ago, this peninsula was ruled by a monarchy. Despite periods of authoritarianism and military rule, the country’s citizens ultimately brought sweeping democratic change through mass movements such as the Candlelight Revolution.

This phenomenon cannot be dismissed as a mere copy of Western systems or a product of foreign influence. Its foundation lies much deeper — in Korea’s own historical and political tradition, particularly the governance culture of the Joseon Dynasty (1392–1897).

Europe’s Age of Absolute Monarchies: Rule Without Representation

During the 17th and 18th centuries, most of continental Europe was dominated by absolute monarchies. France’s Louis XIV famously proclaimed, “L’état, c’est moi” (“I am the state”), embodying a system where legislative, judicial, and executive authority was concentrated in the hands of a single ruler.

Political participation was virtually nonexistent for common people. Parliaments, where they existed, mostly functioned to legitimize royal decrees rather than challenge them. Freedom of speech and press were tightly controlled, leaving little room for dissent.

Joseon’s Minben Ideology: Early Seeds of Public Accountability

Joseon’s political system was different in spirit and structure. It was rooted in Confucian Minben (民本) philosophy, which held that the people were the foundation of the state.

Though kings still wielded supreme power, their authority was institutionally constrained and morally bound. The monarch was expected to govern justly, with an awareness that his words and actions would be scrutinized and remembered.

Key Features of Joseon’s Governance

- Transparent Historical Records

The Annals of the Joseon Dynasty (Joseon Wangjo Sillok) were meticulously compiled by independent historians. Kings could not alter or censor what was written, which forced rulers to act with accountability — an early form of administrative transparency. - Channels for Public Petition

The Sinmung-go system allowed even commoners to strike a drum at the palace gate to petition the king directly. This revival under King Yeongjo represented a rare form of institutionalized grievance redress, unprecedented in Europe at the time. - Watchdog Institutions

Agencies like the Sahyeonbu and Saganwon were tasked with monitoring royal conduct and offering remonstrations. Though sometimes suppressed during political purges, they nonetheless represented an embedded mechanism of power checking. - Merit-Based Bureaucracy

Joseon’s civil service exam system (Gwageo) opened limited but real pathways for social mobility based on merit — contrasting with Europe’s mostly hereditary appointment systems.

A Comparative Glimpse: Joseon vs. European Absolute Monarchies

| Aspect | Joseon Dynasty | Continental Europe (17th–18th c.) |

|---|---|---|

| Governance Philosophy | Confucian Minben – people as the foundation of state | Divine Right of Kings – monarch’s power seen as sacred |

| Voice of the People | Appeals by officials, Sinmung-go petitions for commoners | Almost nonexistent; power concentrated among monarch and elites |

| Checks on Power | Sahyeonbu, Saganwon, independent historians monitoring royal actions | Few institutional checks; royal power often absolute |

| Record Transparency | Joseon Wangjo Sillok – independent, unalterable records | Chronicles often glorified monarchs and served as propaganda |

| Appointment System | Gwageo exams allowed merit-based selection (though limited to yangban) | Predominantly hereditary nobility filled key posts |

Note: England is a partial exception due to its early constitutional monarchy, so the comparison here focuses on continental states like France, Spain, and Austria.

Democracy as a Cultural Legacy

It would be misleading to label Joseon a “democracy.” Political participation remained restricted, and many institutional safeguards depended heavily on the character of individual kings. Nevertheless, compared to Europe’s fully centralized monarchies, Joseon exhibited more structured power checks and greater institutional openness to public grievances.

These traditions, though imperfect, nurtured a historical consciousness of accountability that survived into modern times. When Koreans rose up in the June Democratic Uprising of 1987, they were not simply importing Western democracy — they were reviving a native tradition of demanding moral governance and political transparency.

Conclusion: Democracy’s Deep Roots in Korean History

Democracy is not just a system of elections — it is a historical culture shaped over centuries. Joseon’s governance contained early prototypes of transparency, institutional oversight, and limited public input that would later help South Korea achieve one of the most remarkable democratic transformations in modern history.

South Korean democracy, in other words, is no historical accident — it is the flowering of seeds planted long ago.

Read related articles

The Remarkable Journey of South Korea’s K-Democracy – viewrap

view korean version