Today, thanks to refrigerators, we can make ice and enjoy chilled drinks at any time of the year. But in the past, especially in the height of summer, eating ice was a rare luxury. Remarkably, our ancestors had already developed an ingenious system to preserve winter ice well into the summer months. At the heart of this system was the Seokbinggo (石氷庫), or stone icehouse.

What is a Seokbinggo?

A Seokbinggo was a stone-built storage facility designed to preserve ice harvested from rivers and streams in winter. It did not produce ice like modern refrigerators but served as a long-term storage chamber, keeping ice intact until the hottest days of summer.

Historical records also mention Mokbinggo (wooden icehouses), but none have survived; today, only stone icehouses remain as physical evidence of this ancient practice.

Historical Records — Origins of the Icehouse

- Three Kingdoms Period: The Samguk Yusa records that during the reign of King Yuri of Silla (the third monarch), an ice storage facility was constructed.

- Silla Dynasty: The Samguk Sagi notes that during King Jijeung’s reign, the government stored ice for official use, indicating a state-managed ice preservation system.

- Goryeo Dynasty: Records describe how government offices stored ice and distributed it to officials.

- Joseon Dynasty: Major icehouses such as Dongbinggo (East Icehouse) and Seobinggo (West Icehouse) near the Han River, as well as royal palace icehouses, were in operation. While most ice was reserved for the royal court, the Banbing System (頒氷制度) allowed for its occasional distribution to government officials, patients, and even prisoners.

Notable Surviving Seokbinggo Sites

Most surviving Seokbinggo structures date from the Joseon period. The most significant examples include:

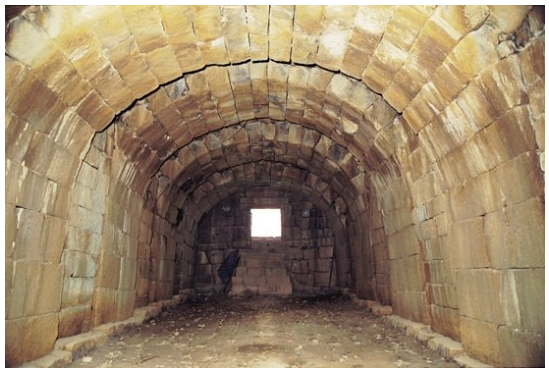

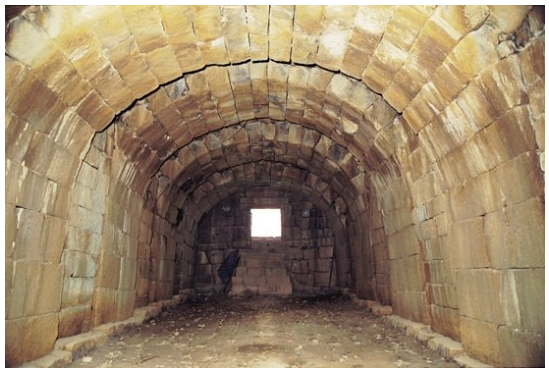

- Gyeongju Seokbinggo – Located within Banwolseong Fortress, it is considered the finest in scale and engineering, designated as a cultural treasure for its advanced drainage and ventilation systems.

- Cheongdo Seokbinggo – Well-preserved, situated within Cheongdo Eupseong Fortress.

- Andong Seokbinggo – Near Hahoe Village, notable for its unique semi-circular ceiling design.

- Hyeonpung Seokbinggo – Located in Dalseong, Daegu, built in the late 18th century.

- Changnyeong Seokbinggo – Known for its efficient sloped flooring and drainage system.

- Yeongsan Seokbinggo – A representative icehouse in the Yeongsanpo area of South Jeolla Province.

(Note: The name “Seobinggo” still survives as a district name in Yongsan-gu, Seoul, a direct legacy of an actual Joseon-era icehouse.)

Engineering Secrets — Why the Ice Did Not Melt

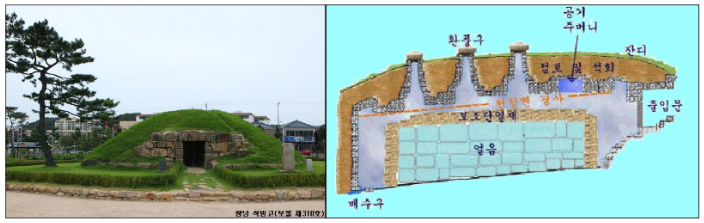

Seokbinggo preservation relied on a combination of site design, structural form, materials, and storage techniques:

- Semi-underground Construction – Partly buried underground to take advantage of the earth’s stable temperature.

- Arched Roof – Enhanced structural stability, improved airflow, and dispersed heat.

- Sloped Floors and Drainage – Meltwater was guided out to prevent humidity buildup.

- Ventilation Shafts – Typically three roof vents expelled warm air and kept cool air low inside.

- Thermal Mass Materials – Thick granite walls absorbed and buffered heat fluctuations.

- Roof Covering – Layers of soil and grass on the roof shielded against sunlight and radiant heat.

- Natural Insulation – Rice straw, chaff, and reeds placed between ice blocks and walls minimized heat transfer.

- Access Steps – Stone stairways allowed workers to enter and stack or remove ice.

This multi-layered design kept ice blocks remarkably intact even in the height of summer.

Ice Harvesting and Transportation

Harvesting (January–February):

- Ice was cut when river surfaces froze thickest, typically into blocks about 1 meter by 70–80 cm, with thickness varying by location.

- Surfaces were scraped clean of snow and impurities, then cut using saws, chisels, and iron hooks.

Transportation Methods:

- Ice Sledges – Pulled across frozen or snow-covered paths.

- Carts/Wagons – Horse- or ox-drawn for overland transport from rivers to storage sites.

- Temporary Ramps – Installed at icehouse entrances for rolling or sliding ice inside.

- Protective Coverings – Straw mats or cloth to prevent melting during transport.

- Labor Mobilization – Large workforces, often mobilized under local government orders.

Stacking in Storage:

- Straw mats laid on the floor; ice blocks stacked with insulating layers of straw or reeds between them.

- Arranged to allow airflow and quick drainage.

Social and Cultural Role — The Banbing System

Ice stored in Seokbinggo served not just the royal table but also medical needs, ceremonial events, and the hospitality of distinguished guests. Through the Banbing System, ice could be distributed to officials, the sick, or even prisoners, reflecting its value as a state-controlled public resource.

Global Comparisons

Similar ice storage facilities existed elsewhere: Japan’s Himuro (氷室), China’s Bingshi (冰室), and Europe’s ice houses. However, Korean Seokbinggo developed distinct engineering and management systems suited to local climate, materials, and centralized governance.

Conclusion — A Block of Ice, A Legacy of Ingenuity

The Seokbinggo was not merely a building; it was a comprehensive system integrating physics (heat and airflow), architecture (structure and materials), logistics (harvesting and transport), and governance (distribution policies).

From winter river ice cutting, to sled and cart transport, to semi-underground stone vaults insulated with straw — every step reflected the wisdom, labor, and resource management of past generations.

Behind every cube of ice we now take for granted lies a centuries-old story of innovation, dedication, and adaptation to nature.

Discover More Insightful Reads

The Honilgangni Yeokdae Gukdo Map: Joseon’s Global Vision in 1402 – viewrap

The Turtle Ship: The World’s First Ironclad Warship and Korea’s Maritime Legacy – viewrap